The chemistry of boric acids and boron is, for lack of better words, rather Unhinged. Unlike it’s relatively (and only relatively) well behaved neighbour aluminium or the ubiqitous carbon, it’s aqueous chemistry involves a lot of polymers, with boric acid forming differently shaped ions depending on the pH and the ions present in solution. One such example is in commonly encountered Borax, which does not crystallize out as just a sodium orthoborate, but instead takes a shape of a tetraborate ion, with it’s weird bicylic structure.

Reference: Crystallography Open Database

In certain conditions, and especially in melts, the reaction can be pushed further into making amorphous giant polymers of boric oxides, which are of use in optics and glassmaking, like for making the widespread borosilicate glass or for synthesizing phosphors by adding a small amount of organic dopant before forming the borate glass matrix.

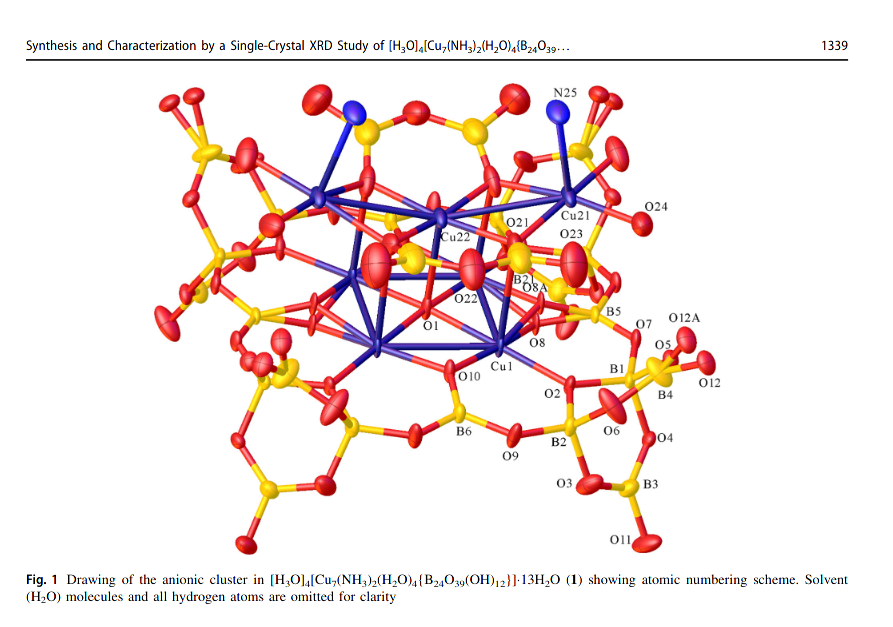

Besides just making large polymeric networks, work has also been carried out in using various metal complexes as templates for assembling ions, allowing us to obtain ions of a well-defined size and structure, avoiding a polycondesation mess that is obtained via plain aqueous chemistry.

Reference: Mohammed A. Altahan, Michael A. Beckett, Simon J. Coles, Peter N. Horton CCDC 1858267: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2018, DOI: 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc20cp36

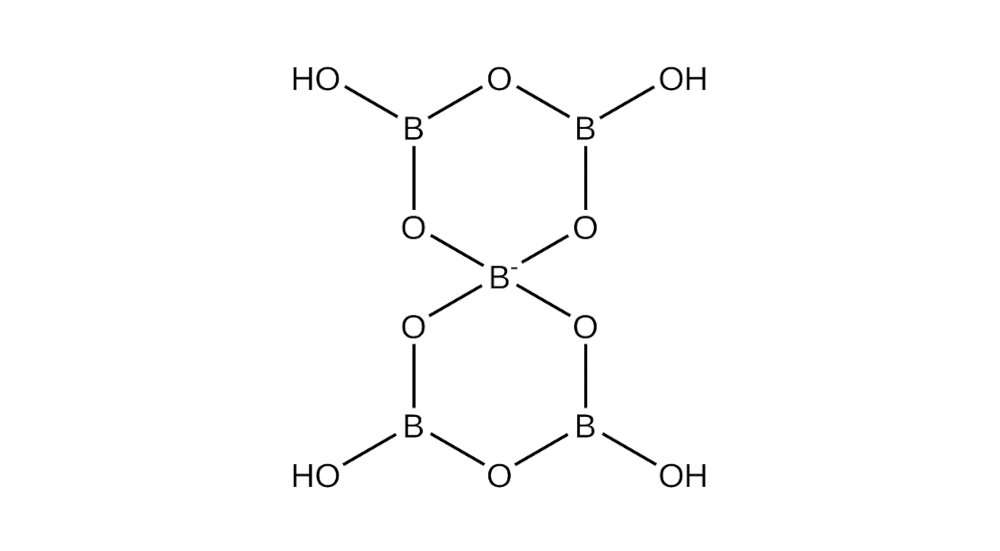

In this writeup, we are replicating the synthesis of a rather small ion, the pentaborate (seen below), although much larger assemblies have been detailed in literature (personally, the biggest I’ve seen was 24 (as seen above))1.

Ethylenediamine Copper Pentaborate

This work is based on a 2017 article by Altahan et al2, with no significant changes made outside of slightly scaling it up because I personally like working on a 0.01 mol scale.

Thankfully, because this compound was synthesized and characterized before at a proper lab, with access to proper X-ray equipment, we can take a look at a a visualization of crystallographic data that was obtained in their work, and see up close the peculiar shape the spirocyclic pentaborate ion takes

Reference: Mohammed A. Altahan, Michael A. Beckett, Simon J. Coles, Peter N. Horton CCDC 1534199: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2017, DOI: 10.5517/ccdc.csd.cc1nhg9x

En Copper Sulfate

The first step is making the precursor complex, bis-(Ethylenediamine) Copper (II) Sulfate, which is trivally synthesized by adding 2.1 grams of neat ethylenediamine to a solution of 4 grams of copper sulfate hexahydrate in 15 ml of distilled water. This provides us with an excess of starting material after precipitation by adding isopropanol. The resulting product is a purple-blue powder, soluble in water giving a deep blue-violet solution.

En Copper Hydroxide

In the next step, 2 grams of the copper complex were dissolved in a small amount of water and a solution of 2.26 grams of barium hydroxide octahydrate was prepared in enough warm distilled water to give a homogenous solution. The hydroxide was added to the metal complex, leading to the precipitation of white barium sulfate, and the replacement of the sulfate anion with hydroxide. The barium sulfate was filtered off and thoroughly washed with distilled water to get the last bits of the soluble hydroxide complex out.

The Pentaborate

To the obtained aqueous solution, 4.4 grams of boric acid were added and the solution was stirred for 30 minutes, with a slight colour change to more purple. The solution was then concentrated down on gentle heat to ~10 ml and left to dry in a desiccator. After a while of waiting, a quite impure product was obtained, containing huge crystals of the target compound, but also a lot of boric acid and an insoluble blue precipitate of copper (meta?) borate.

The work on this complex was resumed only a few months after, as I spent the rest of the summer in a sort of dissociative haze caused by the summer heat and power outages, and honestly don’t recall most of it except for the stuff written down in some of my lab logs. Probably for good.

The resulting solid was then dissolved in a mixture of methanol and water, and gravity filtered to remove insoluble impurities like copper borate, resulting in a purple solution resembling Cobalt (II). The solution was slightly evaporated, and the resulting purple product was separated out via gravity filtration and placed in a vial, at which point the synthesis was finally considered complete.

The final yield wasn’t measured, however it was considerably lowered during the recrystallisation.

Literature

Beckett, M. A. Recent Advances in Crystalline Hydrated Borates with Non-Metal or Transition-Metal Complex Cations. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2016, 323, 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2015.12.012.

Sources

-

Altahan, M. A.; Beckett, M. A.; Coles, S. J.; Horton, P. N. Synthesis and Characterization by a Single-Crystal XRD Study of [H3O]4[Cu7(NH3)2(H2O)4{B24O39(OH)12}]·13H2O: An Unusual [{(H2O)2(NH3)Cu}2{B2O3(OH)2}2Cu]2+ Trimetallic Bis(Dihydroxytrioxidodiborate) Chain Supported by a [{Cu4O}{B20O32(OH)8}]6− Cluster. J Clust Sci 2018, 29 (6), 1337–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1452-9. ↩

-

Altahan, M. A.; Beckett, M. A.; Coles, S. J.; Horton, P. N. Synthesis and Characterization of Polyborates Templated by Cationic Copper(II) Complexes: Structural (XRD), Spectroscopic, Thermal (TGA/DSC) and Magnetic Properties. Polyhedron 2017, 135, 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10876-018-1452-9. ↩